Urgency vs. Decency: Human Rights Violations In Response to Violence

- Alexandra Rae

- Jul 7, 2024

- 8 min read

By Blanka Pillár

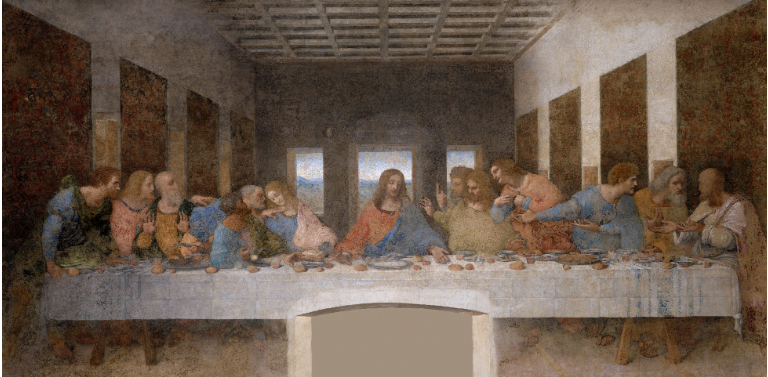

Collage by Marta Castro on Behance

Forced labor and human trafficking (Yun, 2004); violent attacks on journalists (Amnesty

International, 2023); and the use of unlawful lethal force on minorities (Amnesty

International, 2021). What do these alarming occurrences around the world have in common?

They are all human rights violations. Human rights and their violations in various forms are

ubiquitous and multifaceted problems for humanity and the world today, raising questions

such as ‘Are human rights violations necessary to treat issues around the world?’;

‘Is it acceptable to take any action that violates the fundamental rights of another person or

group of people? ’ or ‘What if these violent solutions have some benefits that more

diplomatic solutions lack?’ In order to gain an in-depth understanding of human rights as a

whole, it is necessary to define some key concepts, such as human rights and the obligations

connected to them.

Human rights are ‘the basic rights and freedoms that belong to every person in the world,

from birth until death’ (Equality and Human Rights Commission, [EHRC] n.d.). According to

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - the milestone declaration summarising these

named rights - all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, without

distinction of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or

social origin, property, birth, or other status. The UDHR also states that these universal rights

cannot be arbitrarily taken away; however, they can be restricted if someone breaks the law,

even by violating the terms of any of the treaties (Office of the High Commissioner for

Human Rights [OHCHR], n.d.). From then on, the violation of the human rights of an

aggressor is not a human rights violation but a legally binding restriction (for instance, if an

international organization imprisons a dictator or a terrorist group).

The UDHR also states that human rights are indivisible and interdependent, referring to the

fact that the rights enshrined in the two prominent human rights treaties, the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), cannot be separated from each other.

ICCPR primarily protects individuals from state power (this treaty includes rights like

freedom from slavery, torture, other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment,

fair trial rights, and freedom of thought, religion, and expression). Besides this, the ICESCR

devotes its parties to working toward the provision of economic, social, and cultural rights

(such as the right to adequate housing, health, work, and freedom from hunger). In addition to

these pacts, other treaties aim to end specific abuses and safeguard the rights of marginalized

groups, for example, The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination

against Women (CEDAW) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

(UNCRC). Consequently, a human rights violation is ‘any action or inaction which deprives a

Participant of any of his or her legal rights, as articulated in law’ (Law Insider, n.d.).

All these details are intended to illustrate how crucial and multifaceted intertwined human

rights are. After understanding the importance and interconnectedness of the subject, it ought

to be said that human rights violations are not acceptable, even if they end widespread

violence. This thesis is based on historical examples, current and past social and political

trends, as well as legal definitions.

The first aspect to consider is necessity. Human rights violations are, by all means, the most

drastic ways of dealing with the violence that may occur, but they are not automatically the

most effective.

Under the principle of subsidiarity (EUR-Lex, n.d.), all and any kind of problems should be

tackled at the lowest possible level where they occur; therefore, they should be settled at local

and regional levels first before being taken to the national level. In addition, prevention

(monitoring, reporting, the inclusion of non-governmental organizations) and education can

provide a much longer lasting and more profound solution than violent interventions since

the latter can change the mindset of entire generations, potentially reducing prejudice and the

resulting hate crimes. According to the Human Rights Council panel discussion on the role of

prevention in the promotion and protection of human rights:

"Several delegations emphasized that the adoption of preventive measures was an absolute and

urgent necessity, and that there was a vital need to strengthen preventive approaches to human

rights violations. Some pointed out that prevention was one of the most effective ways to

protect human rights and expressed the view that the prevention of violations of international

humanitarian law and international human rights law was not only necessary but achievable"

(OHCHR, 2014).

Monitoring, mediation, early detection, and open communication policies regarding human

rights can bring long-term benefits, leading to a more balanced, peaceful society open to

diplomatic and democratic solutions rather than violent ones if said diplomatic resolutions

become normalized and are considered the default answer to any emerging conflicts.

Secondly, another crucial issue factor is the people directly or indirectly affected by these

violations. When human rights violations (in the name of violence combating) also affect

rights such as access to health care for all or any other social need (such as the right to

security, culture, water, or the above-mentioned rights to adequate housing, and work)

it directly worsens citizens' quality of life. When it comes to countries where a minority

group is denied access to health care - which is an everyday happening, for instance, for

Kurdish women and children in Iran (Human Rights Watch, 2022) - for political reasons

(such as gender, sexual orientation, migration status, religion, or ethnicity), reports show that

these countries have higher mortality and morbidity rates due to non-communicable diseases

(such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic respiratory disease). Moreover, if any of

these groups are subjected to further regulations, accessing healthcare prevention,

rehabilitation, and additional care services are legally more difficult, resulting in even

worsened life quality (World Health Organization, 2022).

In other cases, even if human rights violations do not affect social needs, there is still a

correlation between poor quality of life and human rights violations. According to multiple

statistics, the country with the worst rule-of-law score is Yemen - where performing violent

acts on minorities in the name of violence prevention and peace, as well as scapegoating, are

highly prevalent occurrences (United Nations News, 2020) - with a rule-of-law index of 9.9

on a 10-point scale, where zero represents the best conditions and ten the worst. In line with

this fact, life expectancy - an essential indicator of the quality of life - in Yemen is 8,3 points

below the world average for men and 6,8 points for women (Statista, 2023; The Global

Economy.com, 2022).

After analyzing the scale, the other side of the correlation can also be observed; the country

with the highest rule-of-law index, according to a 2022 statistic, is Denmark, with a rule-of-

law index of 0.90 (World Justice Project, 2022), and based on the U.S Department of State’s

Country Report in 2022, ‘There were no reports of significant human rights abuses.’ in said

country (United States Department of State, 2023a). If "quality of life is a sign of rule of law"

(Noor, 2016), it can be argued that having an accountable, properly ruled, democratic

government, where human rights abuses are minimized, including in the fight against

violence, can have a significant positive impact on the quality of life of civilians.

Furthermore, if we look at the country with the lowest Human Development Index (HDI),

which according to Human Development Reports, is Niger, a correlation can be drawn

between the volume of human rights violations and the low quality of life, as Nigerien

citizens are subject to terrorist group showdowns, forced disappearances, inhuman treatments

and punishments, armed bandit groups, smugglers, drug and human traffickers. In addition,

according to the 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices by the U.S. Department

of State, ‘There were numerous reports of arbitrary or unlawful executions by authorities or

their agents. For example, the armed forces were accused of summarily executing persons

suspected of fighting with terrorist groups in the Diffa and Tillaberi Regions’(United States

Department of State, 2023b). Even if any of these named actions in any country stop or end

any violence, they also enormously degrade the daily quality of life of the countries’ citizens

by progressively eroding their political, social, and economic rights, as well as provoke more

violence and potentially begin a worsening cycle of further brutality and human rights

violations.

A reasonable counterargument is that ending violence by violating human rights is much

quicker than waiting for diplomatic agreements to be adopted. But is it worth sacrificing

significant numbers of human lives, degrading the quality of life of civilians, on the altar of

speed, rather than pursuing more peaceful, longer lasting, and more positive long-term

solutions that will stop violence as much or more? Besides this unambiguous comparison, a

crackdown’s turnaround time may indeed be faster; however, if it is acknowledged that the

government alone should not be entrusted with a task of such magnitude and methodology in

the name of democracy due to its often biased tendencies (see current and past historical

examples above, and not forgetting the fact that one of the most fundamental human rights

treaties, the ICCPR particularly protects individuals from state power for a well-grounded

reason), engaging a larger group (for example, the people of a country in a referendum or

other expression of opinion) would also take considerable time. In the case when these

violations are not carried out by a centralized force such as the government but by an

individual or a group, the borderline between legitimate violations against actual violence and

between terrorism or various hate crimes is extremely relative, thin, easily contested, and

questionable. In addition, if responses involving human rights offenses to different acts of

violence were normalized, it could reduce the need for diplomatic negotiations and

communication between people and various groups, thus increasing microaggressions in

everyday life.

In conclusion, acknowledging that resorting to human rights violations to address widespread

violence is an untenable course of action is imperative. Not only are these violations deemed

unnecessary, but their lingering consequences on people's lives and the authoritarian nature

they entail are highly problematic. Even if human rights violations in response to widespread

violence may prove to be temporary resolutions, nevertheless, they can be considered

perilous band-aid solutions as other methods are proven to be not only more effective and

long-lasting but much safer and beneficial for citizens around the world.

Bibliography

Amnesty International (2021), “Iran: Security forces use ruthless force, mass arrests

and torture to crush peaceful protests,” Amnesty International [Preprint], Available

force-mass-arrests-and-torture-to-crush-peaceful-protests/.

– – (2023), “Russia: Investigate vicious attack on Elena Milashina and Aleksandr

Nemov in Chechnya,” Amnesty International [Preprint], Available at:

attack-on-elena-milashina-and-aleksandr-nemov-in-chechnya/.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (n.d), What are human rights?, Available at:

EUR-Lex (n.d.), - subsidiarity - EN - EUR-Lex, Available at: https://eur-

Human Rights Council (2014), Summary report on the outcome of the Human Rights

Council panel discussion on the role of prevention in the promotion and protection of

human rights, Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/calls-for-input/study-role-

prevention-promotion-and-protection-human-rights.

Human Rights Watch (2022), “Iran: Brutal Repression in Kurdistan Capital,”

capital.

Law Insider (n.d.), Violation of Human Rights Definition, Available at:

Noor, N.F.M. (2016) “Rule of Law: Its Impact on Quality of Life,” European Journal

of Interdisciplinary Studies, 4(1), p. 143. Available at:

OHCHR (n.d.) What are human rights? Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/what-

are-human-rights.

Statista (2023), Highest human rights and rule of law index scores in 2022, by

country. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1256220/highest-human-

rights-and-rule-of-law-index-by-country/.

The Global Economy (2022), Human rights and rule of law index by country, around

the world, Available at:

United Nations News (2020), COVID-19 scapegoating triggers fresh displacement in

Yemen, warns migration agency (2020). Available at:

United States Department of State (2023b), 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights

Practices: Denmark, Available at: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-

human-rights-practices/denmark/.

– – (2023b), 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Niger,

practices/niger/.

World Health Organization (2022), “Human rights,” www.who.int [Preprint],

Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health.

Yun, G. (2004), Chinese Migrants and Forced Labour in Europe, Available at:

Comments