The End of The World as Told in Literature: How Station Eleven’s Pandemic Mirrored Our Own

- Breanna Crossman

- Feb 26, 2023

- 5 min read

By Alexandra Rae

In the Shakespearean tragedy meets sci-fi dystopian nightmare known as Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, the world is split into two: the before and the after. Before Mandel’s fictionalized Georgia Flu runs rampant across the globe, life retained the kind of normalcy we knew before the disastrous year of 2020 – people could visit families around the holidays, take flights to Malaysia just for the hell of it, go to grocery stores without tape markings lining the floor at the checkout line, maskless faces smiled in selfies shared on social media when there were things to smile about and the Internet was not yet obsolete. The aftermath of the Flu took all of this and more within this novel, making the similarities between Mandel’s version of the apocalypse and the events of the past three years in our world striking enough to analyze through my personal lens of both a lover of apocalyptic literature and a young person who has witnessed our world crumble and learn to begin again.

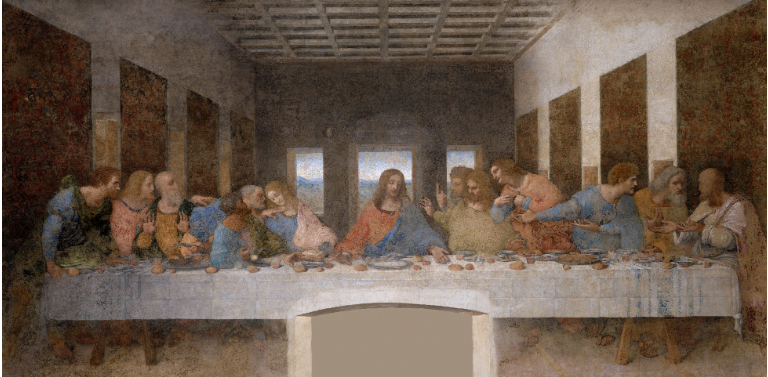

(Rosana Garcia/Pinterest)

At the beginning of the end, hospitals became overwhelmed with patients experiencing severe flu-like symptoms. Jeevan, one of the main characters in Station Eleven who is prone to panic attacks and hypochondria, found out about the Georgia Flu from a friend of his who worked at the hospital, telling him over the phone, “‘It's a full-on epidemic. If it’s spreading here, it’s spreading throughout the city, and I’ve never seen anything like it’” (Mandel 20). Let us return to the United States in early 2020, where, by March 31, there were over 196,000 confirmed cases and over 4,000 deaths from the first Covid variant (The Covid Tracking Project). Think back to the horrors displayed on television of body bags stacked outside hospital doors, exhausted nurses covered in PPE gear as they wheeled more sick people into the confinements of their understaffed and under-resourced hospitals, hoping they would still be alive to hug their children after their 20-hour shift was over – it’s something that many people never believed they would see and, yet, there it was, our ruined reality right there in front of us. Just like the chaos that spiraled from the contagion we faced, the Georgia Flu within the novel quickly led to hospitals being shut down and stores becoming ransacked (thankfully, though, this happened in our world from doomsdayers and large families buying all the toilet paper in Walmart and not a “purge-like” scenario causing people to steal everything right off the shelves). The initial collapse of normal life in 2020 and in Mandel’s world happened at similar rates, with similar casualties that followed.

This epidemic we faced only grew more eerily similar to the one Mandel crafted six years before COVID changed the world. By the end of January 2020, the Trump Administration set proclamations in place to ban entry into the country from areas with high case counts, which quickly spread to air travel in and out of the country being temporarily banned altogether (Congressional Research Service, 2020). Flights were canceled, leaving many people stranded far away from the places they knew as home. Within Station Eleven, air travel was also an aspect of everyday life that ceased to exist because of the flu, though on a more permanent scale: “No more flight. No more towns glimpsed from the sky through airplane windows, points of glimmering light; no more looking down from thirty thousand feet and imagining the lives lit up by those lights at that moment. No more airplanes…No more countries, all borders unmanned” (Mandel 31). Diaspora became all that was known for the characters within Station Eleven, just as it has always been for the immigrants and lost individuals affected by the halt of air travel during the height of COVID. This distribution of stranded souls in Mandel’s world and our own exhibits how tethered we are to each other, how even the kindness of strangers or the light coming from unknown houses in unknown lands is enough to bring us comfort when we have lost everything else – except each other.

The importance of art and how it is a force that can survive above all else is another shared aspect of our pandemic and the end of the world in Station Eleven. Twenty years after the Georgia Flu kills 99% of the world’s population, the Traveling Symphony travels by foot and horse caravans to perform for groups of people that live in gas stations and Walmarts, which are the closest thing their world now has to towns. The combination of actors and musicians within this group specializes in Shakespeare plays, performing works like King Lear and A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the survivors of the apocalypse. Why spend their lives on the road, risking their survival and indulging in their art forms while most people worry about staying alive? According to Dieter, one of the members of the Traveling Symphony, people “ ‘want what was best for the world’...He himself found it difficult to live in the present. He’d played in a punk band in college and longed for the sound of an electric guitar” (Mandel 38). In this world, and in any world with human beings that have the ability to create and express themselves, art is what was best for the world before the act of creation became too dangerous, too unthinkable to attempt. It is what people turned to feel alive again.

And what did we turn to? We turned to Tik-Tik, to make dancing videos with our siblings in our messy living rooms and uncut yards. We turned to banana bread, to Tiger King, and long walks discussing God and our new favorite books with our families. We turned to podcasts, to underground indie albums from 2004, enhancing the experience of our nostalgia-fueled listening with wired headphones we found in the bottom of our backpacks. We turned to tie-dying t-shirts and painting sunsets on blank canvases we found in our basements from too many Christmases ago and staining our hands from trying out a new hair color and writing shitty poetry and anything that helped us feel rooted in the magic that existed in the before. It is when we lose everything that we attempt to create anything – to take us back, if only for a moment.

For anyone looking to read a story about love and loss and worlds shattering and colliding, I highly recommend Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel. It was a book that made me rethink my own experience at the beginning of the pandemic and how fraught our world is. How anything can both tear us apart and bring us all together.

Works Cited

“COVID-19: Federal Travel Restrictions and Quarantine Measures.” Liu, C. Edward, COVID-19: Federal Travel Restrictions and Quarantine Measures (congress.gov). Updated May 28, 2020. Accessed 22. Feb. 2023.

St. John Mandel, Emily. Station Eleven. 2014. Alfred A. Knopf.

“Totals for the US.” The COVID Tracking Project, https://covidtracking.com/data/national. Accessed 22 Feb. 2023.

Alexandra Rae (she/her) is a 20-year-old aspiring writer from the U.S. studying Creative Writing and Public Relations & Advertising at Point Park University. She loves exploring all genres, but her favorites are Creative Non-Fiction and Poetry. She is also a content writer for The Young Writer's Initiative (@TYWI on Instagram) and runs her own writing account as well

(@theresonationofalexandra). Her biggest writing inspirations are Taylor Swift, Lauren Slater, Stephen King, and Joy Harjo.

Comments