The Absurdity of Waiting By Blanka Pillár

- Jun 4, 2023

- 3 min read

‘We were respectable in those days.’ - says Vladimir at the beginning of one of the most influential absurdist dramas in world literature, Waiting for Godot. The genre's worldview, which unfolded in the wake of the hopelessness and disillusionment of the Second World War, is characterised by a sense of the utter purposelessness of existence, a crisis of social and personal presence, of classical communication and human relationships. Working only with spartan, barren settings, plain language and indeterminate time and space, the role of non-verbal communication (especially body language) and non-linguistic means of expression (pauses, silence) in conveying meaning is increased.

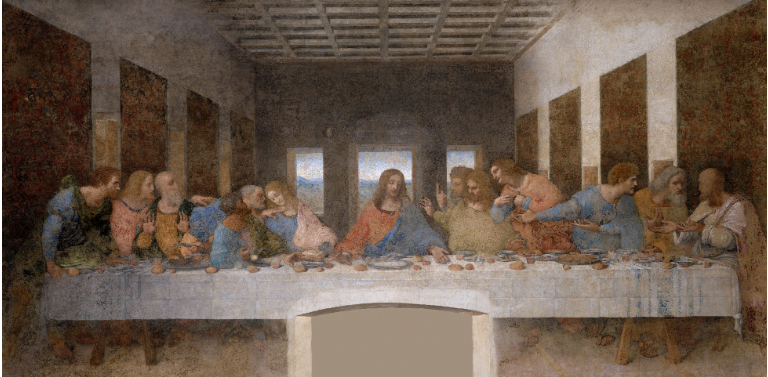

Via: Francis O’Connor Design

In many ways, Beckett returns to the medieval origins of morality plays and mystery plays in this drama. The primary characteristics of morality play, allegorical characters representing general types of people with different ideals, and a perspective determination are all present in the 1952 work, with the difference that while the worldview in the former is based on Christian faith, in the latter, it is based on philosophical deductions. According to the author's instructions, the play is not concrete or definable in space and time; its setting is a metaphorical space with only a highway and a tree. With these two archetypes of life and the way they are represented, the worldview and the depreciation of the drama are immediately revealed; the road, in fact, loses its meaning; it comes from nowhere and goes nowhere, the perished, withered tree - which also evokes the Tree of Eden by involuntary association - is no longer a symbol of knowledge, life or the beauty of nature, but somewhat of man's alienation from nature, the possibility of death and the cross-tree. Every aspect of the background, from the dark sky to the steep edge of the peat bog, to the indeterminate ditch where Estragon spends the night in Act I, at most, creates a sense of contingent and uncertain familiarity for the characters. They do not know if they are waiting in the right place (‘What are you insinuating? That we've come to the wrong place?’ - Vladimir) or if they were in the same area yesterday (‘We came here yesterday./ Ah no, there you're mistaken.’). These components reveal the homelessness, monotony and hopelessness of existence. The underlying realm of the state of being represented by the symbolic space also has a substantial, meaningful role; it contains humanity's history, philosophy, art and culture. The manufactured objects of everyday life have become alien to those living in the cold and unfamiliar landscape that can be interpreted as the world around them. Thus, Vladimir's head does not fit his hat, Estragon's feet do not fit his shoes, and even the most basic actions are a problem for them ((‘giving up again [on taking off his shoes]). Nothing to be done.’). The work's circular structure and the acts' interchangeability reinforce this philosophical content: everything is repetitive, and Nothing changes.

The characters in the play are abstractions that can be set in complementary pairs (Vladimir-Estragon, Pozzo-Lucky). While Vladimir is the expressive, spiritual man, Estragon is the more down-to-earth, instinctive, acting being. This difference is also reflected in their names (dire: to say; go: to go), but despite the differences, they are not opposites since their constant interdependence is undeniable; if they were not together, they would only exist as half-men (‘Don't touch me!/ Do you want me to go away?/ Gogo! Did they beat you?/Gogo! Where did you spend the night?/Don't touch me! Don't question me! Don't speak to me! Stay with me!/ Did I ever leave you?/ You let me go.’).

The nature of the figure of Godot, who moves the characters, is one of the drama's most complex, complex and obscure questions. Estragon and Vladimir look to him to give their lives meaning and redeem them from idle waiting. Linked to the question of redemption is the dilemma of the Lator's salvation, the ongoing idea of repentance and suicide. The play does not answer who Godot is, preserving the uncertainty of humanity represented by Estragon and Vladimir. It could be a God in a godless world (the English God is a French God with a diminutive, although Beckett rejected this interpretation) who no longer exists because of the sins of the human race (see Nietzsche - Gott ist tot! Gott bleibt tot! Und wir haben ihn getötet!1), or a general ordering principle in which everything falls into place and thus existence makes sense.

1 God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!

Blanka Pillár (she/her) is a sixteen-year-old writer from Budapest, Hungary. She has a never-ending love for creating and an ever-lasting passion for learning. She has won several national competitions and has been a columnist for her high school’s prestigious newspaper, Eötvös Diák. Today, she is not throwing away her shot.

Comments