“Miss Saigon”: Unmasking the Drama, Debate, and Diversity Behind Broadway’s Spectacle

- Alexandra Rae

- Jun 8, 2024

- 6 min read

By Cailey Tin

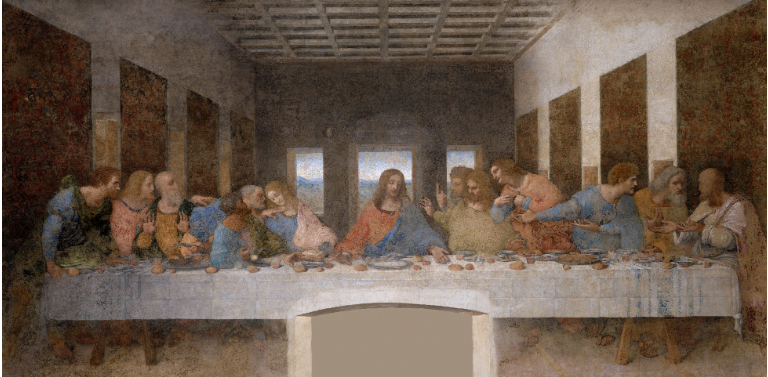

Image from Pinterest

The loud blades of the helicopter pierce the sky like a meteorite, acting as the rarest, only source of hope for those trapped in the trenches of the Vietnam War. With pulse-pounding intensity, the aircraft brims full of desperate citizens before turning its back on the locked gate, flying away with the dreams of those who yearn for a better life. Among those left behind is Kim, watching in defiance as her true love leaves her for a country she often envisioned with her mind’s eye: a place of distant promise.

As this iconic scene from Broadway’s legendary production Miss Saigon etches itself into memory, it leaves behind a lingering sense of intrigue. Filipinos, having grappled with their own fight for freedom, often leave the theater curious about the real-world events behind the play. You may wonder: how are we supposed to respond to the portrayal of the Vietnam War—does this address or perpetuate stereotypes about Asian culture? How intense were the controversies surrounding the representation of Asian characters? And how powerful has theater become in shaping societal norms and values?

Okay, maybe you didn’t wonder about any of those but instead: How do they keep the actor playing Kim's three-year-old son so well-behaved during the emotional scenes? Does the poor kid wish his “mother” could stop belting her lungs out to an incredibly long lullaby about how she would “Give My Life For You,” and just let him sleep? But let’s go back to the original questions. Such thoughts should be prodded on because understanding the controversies and complexities surrounding Asian characters and Asian history will help us unpack broader issues within the realm of theater and representation [as Asians, it’s vital or something like that]. Get your popcorn ready and prepare for a deep dive into the heart of Miss Saigon as we peel its layers of drama, controversy, and cultural significance. Oh wait, no popcorn allowed in theaters! Imaginary food will do.

Perhaps the biggest behind-the-scenes controversy Miss Saigon faced surrounds its casting. The Engineer, who has repeatedly taken advantage of Kim, is Vietnamese pimp—someone who controls or exploits prostitutes. He has traditionally been played by white actors in yellowface makeup, such as Jonathan Pryce in the original Broadway production. This casting of non-Asian actors in Asian roles has been accused of adding to Hollywood's streak of whitewashing. It doesn’t help that the portrayal of The Engineer as manipulative and desperate for the “American Dream” reinforces the stereotype of the "scheming" Asian man, which suggests that Asian men are excessively materialistic and cunning when it comes to money.

Now, why do issues like white casting choices remain prevalent throughout history? The answer is surprisingly no-brainer: casting choices are influenced by the precedent set by previous productions. For example, if you notice a classmate using their phone during class without consequences—maybe it’s only because they haven’t been caught yet. But let’s say you aren’t aware the rule exists, so you’re likely to use your phone too. Now, imagine all your classmates were using their phones. Because everyone’s doing it, there may never come a time where you pause to wonder, “Is it really allowed?” Similarly, when all previous productions have white actors playing Asian characters, subsequent productions are inclined to follow suit without thinking too hard about how this impacts marginalized groups. Spoiler alert: it has immense impacts, of course, through perpetuating stereotypes and lessening opportunities for Asians to portray their heritage onstage. Worse, it reinforces the notion that Asian stories are only worth telling when filtered through a Western lens.

But this blatant ignorance extends beyond casting choices. Despite the Vietnam War setting the plot to motion, critics are upset that Miss Saigon brushes over the wartime backdrop of the story, condensing years of social upheaval into a romanticized narrative. At its heart, Miss Saigon’s main focus is the love story between an American GI and a Vietnamese woman. But by doing so, the storyline often glosses over the intricacies of the war, such as the geopolitical motivations behind U.S. involvement, the experiences of different groups within Vietnamese society, and the long-term consequences for the country.

However, on the other hand, some viewers believe that focusing on Kim and Chris’ love is key to crafting three-dimensional characters. They contend that the amount of attention the script focuses on the characters’ romantic feelings is just right. After all, the shortcut to touching the audience’s hearts is through emotion, even if it means sacrificing the show time that could’ve been used for better fleshing out the Vietnam War’s circumstances. But too much focus on the characters made them more open to the audience’s expectations and skepticism, with character portrayals often seen as problematic.

This concern stems from the narrative imbalance and inaccuracy between Miss Saigon’s characters and the real struggles of Vietnamese people, reducing them to background characters in their own story. While the musical (obviously) has Vietnamese characters, critics stress that they’re often portrayed in ways that merely serve to advance the arcs of American protagonists. For example, the brunt of what was shown in Kim’s storyline highly revolves around her sacrifices for Chris rather than other, equally important facets of her life, such as experiencing poverty, losing her parents, and fostering female relationships. People fear the play reduces her to a subservient, passive plot device. And are they wrong, though? Kim’s character is primarily defined by her suffering and victimization. However, some argue that the self-sacrifice she experiences reflects the reality of Vietnamese orphan girls. They contend that giving her more agency would be unrealistic given the harsh conditions of her situation, and doing so would further exacerbate the already sidelined story of Vietnamese women.

Another character that critics argue isn’t fully developed is the Engineer, albeit his generous amount of screen time. Critics point out that his actions are only instrumental in moving Kim and Chris’ relationship forward, from when they first met in Vietnam to their reunion with Tam near the end. It’s as if The Engineer solely serves to mobilize the plot rather than to be explored as a human being with a unique backstory, struggles and personal motivation. Besides Kim and the Engineer, other Asian characters are thought of as “representatives” of a broad category rather than individual people with separate personalities and lives.

Despite the controversies, “Miss Saigon” remains a popular and influential musical. It has been adapted into a film and revived numerous times on Broadway and in theaters around the world. Because of this, discussions—some friendlier than others—are still ongoing about whether the play serves as a good tool to educate audiences about the complexities of war, imperialism, and cultural representation, or if its problematic aspects overshadow any potential educational value. Activists have gone to lengths to address issues like yellowface, stereotypical characterizations, and Western-centric narratives. They’ve gone as far as organizing protests outside theaters where Miss Saigon was being performed, creating petitions, and engaging with theater companies.

Additionally, because of its prominence, there is a stronger need for criticism to be examined to create change for the better. So what has been done about these controversies? They had to be acted upon—pun intended—because Miss Saigon has the popularity reach to make a huge change in today’s entertainment, whether good or bad. It’s one of the earliest Broadway shows in a predominantly Asian setting—with the most commercial success thus far—so changes have already been implemented to address diversity issues. These include revisions to the script to provide more nuanced portrayals of characters and their relationships, as well as increased opportunities for diverse casting, particularly for Asian actors in key roles. If you caught Sir Cameron Mackintosh’s "Miss Saigon" this month at the Theater of Solaire, Manila, you'd notice that Kim and the Engineer are portrayed by Asian actors Abigail Adriano and Seann Miley Moore, respectively.

Additionally, there has been a push to put diverse perspectives in positions of power within the production process, such as directors, writers, and producers, to ensure a more inclusive and authentic representation. These measures aim to make "Miss Saigon" more approachable and culturally sensitive as a production, fostering greater understanding and dialogue surrounding its themes and messages. Thus, while Miss Saigon continues to spark debate and critique, the efforts to address its controversies and promote diversity within the production signify a step towards more inclusive and culturally sensitive storytelling in theater.

Comments