The Memory of A Man: Demystifying The Absent Father in Nick Flynn’s Memoir by Alexandra Rae

- Breanna Crossman

- Feb 6, 2024

- 7 min read

“Many fathers are gone. Some leave, some are left. Some return, unknown and hungry. Only the dog remembers.”

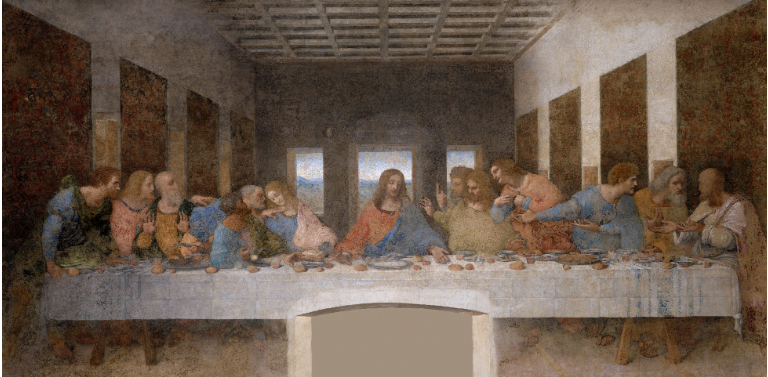

Art by Claudia Gaede, @gaede.claudia

These words come from Nick Flynn’s poetically-charged memoir Another Bullshit Night In Suck City (page 23, the chapter “ulysses”). In it, he details his early adolescence working in the homeless shelter in which his estranged father would arrive one day, leading to an examination of the “self” (the addictions, predispositions, interests, and physical features that make an individual separate from who they came from) and the “father” (a mystery figure; a complete enigma; the thing the “self” often cannot escape from) as this unco relationship develops.

I did not go into this book thinking I would relate to it in any way. What would I have in common with a man who spent his summers living on a boat in Provincetown and his winters driving the streets of Boston, where every figure huddled under a frozen blanket could be his father? I grew up in the suburbs of Ohio, Florida, Tennessee – all states in which my family and I had a place to call home. I had a public school education, a desire to go to college right after I graduated. I had no real concept of what it meant to be homeless until I fulfilled my desire and left home for a private university in a city filled with people on the streets without shelter, food, and, often, sympathy from those that walked by them. I had (and still have) all the makings of a privileged life in America. But at the very core of my childhood, Flynn and I were missing the same thing: our fathers.

I grew up without knowing my biological father. I mean this both in the physical sense and the intuitive sense. When my mom left the house to go to work or the grocery store, my body knew she was gone. A deep mother-sized well would open up in my stomach. I would recognize this void and cry for hours on end until she returned. I would ask where she went, when she would come back to me. I never questioned where my father was. Even as a child, I knew he was never going to come home.

His absence from my life didn’t hurt me the way it could have hurt me, had his non-appearance transpired as a disappearance instead. My father was never there long enough to bring me the kind of pain that would have come with knowing him. Not having contact with him simply made me more aware of the role of “the father” in our society; the need to have a person, a body to bring to the daddy-daughter dances at school or have a cookout with on the third Sunday of June. By not having this, I, like Flynn wrote in the chapter “ulysses” on page 24 of Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, came to realize that “all my life my father has been manifest as an absence, a nonpresence, a name without a body.”

For those of us learning to navigate the world with only one biological parent in the picture, we are often left with an uncomfortable amount of questions, assumptions, concerns, and stories from other people about how to deal with our loss. Their misplaced empathy revealed to me that absent fathers were prevalent enough to be understood, at least on the surface level, by our society. But when talking about how or why his absence came to be, I often was met with widened eyes or flashes of a nervous smile that told me, I don’t want to know. It is easier to believe that the missing pieces in each of our lives are the same.

Absent fathers are not myths or the bogeyman whispered about in ghost stories.

Sometimes they are apparitions of the man that should have been in your life. Sometimes they become the person you help pick up from the ground, never knowing if they would do the same for you.

For Nick Flynn, his father, Jonathan Flynn, became an amalgamation of both of these throughout the course of his life. Homeless, struggling with alcoholism, tiptoeing between the right and wrong side of the law – Jonathan was a difficult man to handle, both in life and in writing. Perhaps this is why Flynn’s memoir is told in vignettes, with his poetic undertones guiding readers towards a space where reality becomes a dreamscape we all fall into. Take, for instance, the two-page chapter “two hundred years ago”, which doesn’t simply ask readers to imagine their lives in some ancient past we’ve never experienced, it pushes the readers into this foreign reality as a way to reshape our perspective on his life: “If you had been raised in a village two hundred years ago, somewhere in Eastern Europe, say, or even on the coast of Massachusetts…they would all know that the town drunk or the village idiot was your father” (26). In Flynn’s narrative, his father is my father is your father is all of our fathers, the crux we often cannot escape from.

There is no escape for Flynn as he discovers and forever immortalizes his father’s legacy within his memoir. Just as he raises the moral question of, “For if you are not responsible for your own father, who is? Who is going to pick him up off the ground if not you?” (27), he also makes allusions to Ham, son of the biblical Noah, who “saw his father drunken and naked, and for this he was cursed, and all of his offspring, and the races that led from these offspring, accursed forever” (237). Flynn sees himself as the accursed Ham, forever undone by his father’s vices. He also knows, however, that it will be his hand that reaches out to help him off the ground, his intrinsic need to keep the thread between father and son uncut that will save Johnathan. For the estranged children of the world, our way of loving the ones who left us are often a juxtaposition of commiseration and rage.

As readers of Another Bullshit Night In Suck City learn throughout the book, Flynn’s feelings towards his father only became more complex when Johnathan suddenly appears at the Pine Street Inn, the homeless shelter he was working for in Boston. Flynn writes in the chapter “mayberry rfd” that “When he first arrives he has one eye unmoored, having been cross-eyed for years. It floats in his head like a ghost satellite” (214). He doesn’t quite know what to do with Johnathan being in close proximity to his life again, as he was used to only seeing him sleeping on park benches every few months. Flynn asks and answers his own question by the end of this chapter by letting the blankness of the page, the silence it represents, speak for him: “A blustering, damaged man, but many are worse off. Where else is he to go?” (214). Just as I knew my father was never meant to come back to me, Flynn knew his father was always meant to come back to him.

There are many ways to see the father, to move the camera to capture him in a different light. I have sifted through my own mental daguerreotypes of my father to see what perhaps I could not see before. To the people that knew him, Jonathan Flynn was a drunk, a madman, a nightmare tearing through the streets of Boston. His son, however, came to know him for all that he was beyond the consensus of the crowd, especially in their days of crossing paths at the Pine Street Inn. At the beginning of their days together in the shelter, Flynn offered his father a quiet acceptance; a silent truce that let Johnathan know he could stay. But Johnathan could only give back what he knew: a refusal to behave within walls after being outside of them for so long. Flynn writes in “the pine street palace” on page 232:

“Passing through the lobby I see my father, upright and ranting, his head lolling from side to side, his naked body wrapped in a sheet. I walk past him, past my co-workers, who had spent the last hour wrestling him down from the showers, who had finally given up trying to get the motherfucker dressed again…I’d never seen this before, never seen a man dressed only in a sheet in the Brown Lobby. Roman, almost Imperial.”

Here, Flynn sees his father as a king, ruling the Pine Street Inn with his refusals to get dressed and indignation towards anyone who wanted him to be anyone other than who he was. The lens in which he viewed his father was changed – Jonathan Flynn wasn’t a madman or an unhoused person looking to create chaos. He was simply a man who had lost everything in his life, and now his son was bearing witness to the consequences of this loss. He was a warning, an embodiment of the prophecy Flynn tried not to follow. Sometimes, fathers can be this, too. All of our fears living in the flesh of a man, just as scared as us.

I don’t think I’ll see my father for a long time. I’ve learned to accept being a daughter with half of a past to cling onto. There is a part of me, though, that has wondered what it would be like to see him out in the world, to not prepare for his presence and have to face it anyway. For him to become someone real, to become something more than the memory of a man who was never really there, seems improbable. But I only know his absence.

Flynn speaks to his own experience of once only knowing fragments of his father to understanding more about him than perhaps anyone else. Even as my life story is wildly different from Flynn’s, I know what it means to unremember the blood you carry in your veins, and then remind yourself of who you came from when you’re cut open.

Alexandra Rae (she/her) is a 20-year-old aspiring writer from the U.S. studying Creative Writing and Public Relations & Advertising at Point Park University. She loves exploring all genres, but her favorites are Creative Non-Fiction and Poetry. She is also a content writer for The Young Writer's Initiative (@TYWI on Instagram) and runs her own writing account as well

(@theresonationofalexandra). Her biggest writing inspirations are Taylor Swift, Lauren Slater, Stephen King, and Joy Harjo.

Comments